Shoebill: Enigmatic Giant of the Swamps

In the vast wetlands of central and eastern Africa, a towering avian sentinel silently patrols the marshy waters, casting an imposing figure against the horizon: the shoebill. With its prehistoric appearance and mysterious demeanor, this enigmatic giant of the swamps captivates the imagination of all who encounter it. Join us as we venture into the realm of the shoebill, unraveling its secrets and celebrating its unique place in the natural world.

Amazing Fact:

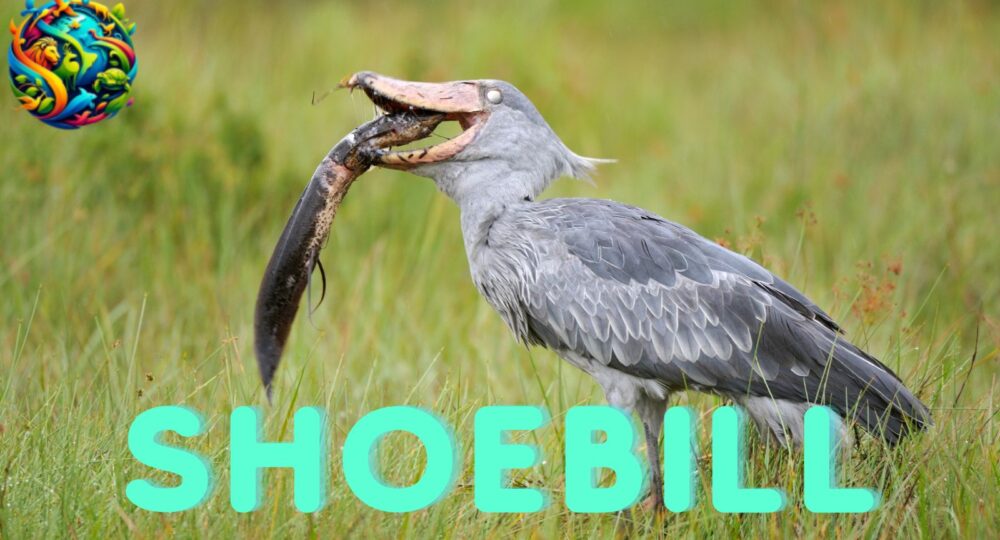

The shoebill boasts a remarkable set of features, including its iconic shoe-shaped bill, which can measure up to 9 inches (23 centimeters) in length. This formidable beak is perfectly adapted for capturing prey such as fish, frogs, and even small mammals, making the shoebill a fearsome predator in its wetland habitat.

Habitat/Food:

They are primarily found in tropical freshwater swamps and marshes across central and eastern Africa, where they stalk the shallow waters in search of prey. Their diet consists mainly of fish, amphibians, reptiles, and occasionally small mammals and birds, which they capture with lightning-fast strikes of their powerful bills.

Appearance:

The shoebil is instantly recognizable for its distinctive appearance, characterized by its large size, broad wingspan, and towering stature. It has a massive, bulbous head adorned with piercing yellow eyes and a massive, hook-tipped bill that gives it a somewhat prehistoric appearance—a testament to its evolutionary lineage.

Location:

They are native to the wetlands and swamps of central and eastern Africa, with populations found in countries such as South Sudan, Uganda, Tanzania, Zambia, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. They prefer habitats with dense vegetation and abundant prey, where they can hunt and nest in relative seclusion.

Predator & Threat:

Despite their imposing size and formidable bill, they face threats from habitat loss, pollution, and human disturbance in their wetland habitats. Additionally, they may fall victim to predation by large birds of prey, crocodiles, and other predators that share their marshy environment.

Mating:

They are solitary birds for much of the year, coming together only during the breeding season to form temporary pairs. Courtship rituals may involve elaborate displays of bill-clapping, head-bobbing, and vocalizations to establish pair bonds and secure breeding territories. Female shoebills typically lay one to three eggs in a large nest constructed from reeds and vegetation.

How They Communicate:

Communication among shoebills primarily involves vocalizations, body language, and visual displays, including bill-clapping, head-bobbing, and posturing. They may use these behaviors to assert dominance, attract mates, and defend territories in their wetland habitats.

Movies on Shoebills:

While shoebills may not be as prominently featured in mainstream movies as other animals, they have occasionally appeared in documentaries and nature films highlighting their unique behaviors and ecological importance. Documentaries such as “The Life of Birds” and “Planet Earth” offer captivating glimpses into the lives of shoebills in their natural habitats.

How It Is Pronounced in Different Languages:

- Spanish: Zapato de agua

- French: Balaeniceps

- German: Schuhschnabel

- Mandarin Chinese: 鸛嘴鸚鵡 (Guànzuǐ yīngwǔ)

- Hindi: शूबिल (Shoobil)

FAQs:

How did the shoebill get its name?

- They derives its name from its distinctive shoe-shaped bill, which resembles a large Dutch clog or wooden shoe. This unique feature is one of the most recognizable traits of the shoebill and sets it apart from other bird species.

Are shoebills related to storks or herons?

- Despite their superficial resemblance to storks and herons, they belong to their own taxonomic family, Balaenicipitidae, and are not closely related to either group. They are classified as part of the order Pelecaniformes, which also includes pelicans, ibises, and other waterbirds.

Can shoebills fly?

- Yes, they are capable of flight and are considered strong fliers, although they are primarily adapted for a sedentary lifestyle in wetland habitats. They may use their wings to travel between feeding and nesting sites or to escape threats, but they spend much of their time wading in shallow waters.

How long do shoebils live?

- They have relatively long lifespans compared to many other bird species, with individuals in the wild known to live up to 35 years or more. In captivity, they may live even longer with proper care and nutrition, making them a long-lived and iconic species in the avian world.

Do shoebills migrate?

- While they are generally sedentary birds that remain in their wetland habitats year-round, some populations may undertake seasonal movements in response to changes in water levels, prey availability, or environmental conditions. However, their migratory patterns are not as well-documented as those of some other bird species.

Are shoebills Endangered?

- They are classified as vulnerable to extinction by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) due to ongoing threats such as habitat loss, degradation, and human disturbance in their wetland habitats. Conservation efforts are underway to protect shoebill populations and their critical habitats.

Do shoebills make good Pets?

- They are wild birds and are not suitable as pets for most people. In addition to legal restrictions on their ownership, shoebills require specialized care, large enclosures, and a diet consisting of live prey. Keeping shoebills as pets also poses ethical concerns regarding their welfare and conservation status.

Are shoebills aggressive?

- They are typically solitary birds that avoid confrontation with other individuals, but they may become aggressive during the breeding season or when defending nesting territories. Their formidable size and powerful bill make them formidable opponents, capable of warding off threats and competing for resources in their wetland habitats.

Author is a passionate writer with an engineering background, driven by a deep love for animals. Despite a successful entrepreneurial career, Saad's true passion lies in sharing his knowledge and insights about animals with the world.

Panda Bear: Gentle Giants of China’s Bamboo Forests

June 13, 2024